Understanding aging may help us defy time

By Hermione Wilson

Despite the better hygiene, health care systems and medical innovation of our modern age, at a certain point the body begins to fail. Skin loses its elasticity, muscles and bones begin to weaken, macular degeneration causes eyesight to fail, and stiffening arteries don’t transport blood throughout the body as efficiently they once did. The immune system doesn’t function as it used to, creating vulnerabilities to infection. Cognitive function may decrease.

Still, we are living much longer than we once did. The average life expectancy has been rising steadily for some time now. According to data from the World Bank, as recently as 1996, Canadians could on average expect to live to about 78 years of age; now they will most likely live at least 81 years, with 85 being the most common age at death according to Statistics Canada.

Of course many people will – and have – surpassed that number. Japan has a high number of centenarians and the Okinawa Centenarian Study is dedicated to uncovering the genetic and lifestyle factors responsible. But if all humans had an ultimate expiration date, it would probably be around the 120-year mark. According to Guinness World Records, a French woman named Jeanne Louise Calment who lived 122 years and 164 days was the oldest person to have ever lived.

So what is preventing us all from living to the grand old age of 120 and beyond? That is the question at the heart of aging research. First, we must understand why we age and according to leading scientists in the field, there are no simple answers. Like teasing out individual threads from a vast tapestry, each researcher seeks to unravel their small part of the mystery. Researchers like Dr. Siegfried Hekimi, who investigates mitochondrial damage and cell dysfunction in animal models at his lab at McGill University, and Dr. Parminder Raina, principal investigator of the landmark Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA).

Why we age

In the lab, Hekimi and his colleagues have been studying mitochondrial function and longevity in mutant mice and roundworms. Hekimi has been examining the biological process of aging for more than two decades and although he and his team were able to extend the lives of their animal models, even he cannot say with certainty why. All he has managed to do so far is rule out possible causes of aging, Hekimi says.

“It’s not caused by free radicals and it’s not caused by mitochondrial dysfunction,” he says. “In our mutants, there’s actually an increase in free radicals, which function like a messenger to turn on stress-resistant mechanisms, and also the processes that are damaging and require ADP [adenosine di-phosphate] are not as intense because we have a reduction of mitochondrial function and that’s why they live long. [But] I still haven’t explained what goes wrong and gets fixed by what I just explained.”

The truth, Hekimi says, is that many of the things people have pointed to as the causes of aging, including free radicals and mitochondrial dysfunction, are actually “a reaction of the organism to a, I believe, still-unknown underlying process.”

There are several possible explanations for why we age, Hekimi says. The most obvious explanation is that our cells accumulate damage and as a result they function less and less well until they eventually breakdown. Hekimi suspects the reasons for this are evolutionary.

“A given organism in the niche it lives in makes a calculation of how much it’s worth maintaining the body, which takes resources, versus reproducing and other things it needs to be doing,” he says. “Depending on what sort of organism you are, you will tend to be living more or less long.”

In other words, it wouldn’t make sense for an animal the size of an elephant to live only a few years when it takes almost 15 years for it to fully mature. That, in evolutionary terms, would be highly wasteful.

A holistic approach

Of course biology cannot fully explain the aging process. A thousand different variables – both internal and external – come into play. For example, we now know that living in isolation from family and friends in the late stages of life can compromise the immune system.

“There is some research emerging that people who are socially isolated actually stop producing some of the cells in their blood that help them fight infection,” Raina says.

“Aging is a complex phenomenon,” he adds. “It’s as much a social phenomenon as it is a biological phenomenon. If you want to understand the biology [of aging], you really have to understand the social aspects of it, or psychological aspects of it or economic aspects of it.”

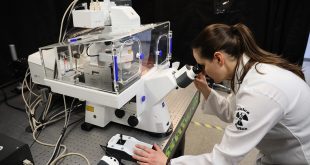

That is why the CLSA has taken a holistic approach to studying aging, Raina says. In addition to gathering medical, social, psychological and economic data from the more than 50,000 participants, CLSA investigators have collected blood and urine samples from 30,000 of that group. Those biomaterials are being stored for posterity at the Biorepository and Bioanalysis Centre (BBC) in Hamilton, ON.

Raina says the CLSA is planning to conduct genetic testing on 10,000 of the participants to see if there are certain genes that result in longevity, similar to genes that cause susceptibility to certain diseases. A group of 5,000 of those participants will be examined for epigenetic biomarkers that will allow researchers to determine their future aging trajectory.

“We want to see how these biological mechanisms change over time and for that we need to recollect every three years when we recontact people,” Raina says. Having all that biological data on hand and the facilities to process it quickly will also allow researchers to do biomarker screenings for disease risk factors. He envisions the BBC becoming an invaluable resource for future researchers, a biobank that will serve many different disciplines and research interests.

“It’s important to keep in mind that aging as a field of research is relatively new,” Raina says. “Much of the focus in this research has been… specific diseases, and we are learning more and more through the biology, the sociology and the psychology of aging that there might be some underlying common pathways that are related to the aging process that actually determine all sorts of different diseases and disabilities.”

Miracle cure

The trouble with aging is that medical research is a tool that has been designed to tackle a specific problem and come up with solutions. For every disease there must be a cure, for every ailment, a treatment. But thinking about aging this way may be the wrong approach.

“So much of medicine has been based around… what’s the issue, what’s the cure,” says Dr. Samir Sinha, the Director of Geriatrics at Toronto’s Mount Sinai and the University Health Network Hospitals. “But there is no cure for aging.”

There are certain treatments and medications out there that we think may slow the aging process or some age-related disease. At one time it was thought that resveratrol, a polyphenolic compound found in red wine (among other things), could inhibit the growth of cancer cells and prevent cardiovascular disease. Studies have even shown resveratrol to increase the lifespan of some animal models, but whether it will do the same for humans is still up for debate.

Similarly, the popular diabetes medication Metformin has also been shown to increase lifespan.

“In a laboratory setting, small studies have shown that [Metformin] might actually impact aging,” Raina says. “People who are taking this drug, they are functionally better and they live longer. So what is it that drug is affecting that changes the underlying biology in these older people that they start to become healthier and live longer? If we start to understand those mechanisms, then we can actually tackle diseases as a complex rather than a one-by-one entity.”

Hekimi regards these treatments that claim to be aging cure-alls with much doubt. No one can point to any one “cure” for aging that is any more miraculous than the simple results of us living better lives, he says.

“There’s no intervention which is any better than what happens for environmental reasons alone,” Hekimi says. “That already tells us something, I think.”

Running down the clock

As a geriatrician, Sinha is more concerned with helping his patients maintain good health and independence in their later years. There are several ways they can contribute to what he calls their “longevity dividend.” Maintaining good social connections, a healthy diet, moderate alcohol consumption, and exercising regularly are just a few.

“We all know that children have a vaccination schedule that ideally they should adhere to,” Sinha says. “But many people forget that older adults similarly have a vaccination schedule that they should be adhering to as well, vaccinations that could prevent common infectious diseases that can cause significant problems and disease burdens in older age.”

Although the numbers show that life expectancy is on the rise, our poor lifestyle choices may balance things out. “The generation before was more likely to have been smoking; this generation coming into aging is less likely to have been smoking,” Sinha says. “Yet this generation that’s starting to age now is more likely to have diabetes and obesity.”

Then again, by the time the next generation starts to age, we may have found a cure for dementia which could that could buy us, on average, five to 10 extra years of life, he says.

“As we approach older age, we’re a very heterogeneous group in that, if you’re lucky enough… to make it to 65, you’re life expectancy resets, you get about 20 more years on average at that point and most of those years are going to be in relatively good health,” Sinha says. “But you can see then that quickly there are some people who are already marching into older age with chronic illnesses and other disadvantages, and other people who actually have a much longer runway ahead of them because they made it that far without any new issues.”

Ultimately, aging is a very complex phenomenon that is difficult to get a handle on, but Sinha is quick to point out that it isn’t all negative.

“I always like to remind people that aging itself is not a disease, but rather it’s a triumph. We should celebrate the fact that we have an opportunity to live almost double the life expectancy that we hoped for over a hundred years ago. That’s a huge gain that we’ve made.”

Photo Credit: Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging

BioLab Business Magazine Together, we reach farther into the Canadian Science community

BioLab Business Magazine Together, we reach farther into the Canadian Science community