Technology and vertical farming are transforming how we produce food

By Mitchell Brown

Located at the corner of Bathurst and Dundas streets in Toronto’s west end, Scadding Court Community Centre is a busy place. Outside its front doors, retrofitted shipping containers house locally owned shops and food kiosks serving delicious street fare reflective of the neighbourhood’s breathtaking diversity; inside, staff and volunteers deliver everything from tai chi and cooking classes to newcomer settlement programs to area residents.

“People are coming from all over to check out the community centre,” says executive director Herman Ellis, adding the centre has hosted visitors from as far away as Finland and Germany who come to see their operation. “It’s one of the oldest technologies on the planet, but the fact we have it here, in the middle of a community centre – that makes it innovative.”

Scadding Court has a long history of promoting food access and security. It prides itself on being one of the first community centres in Canada to rip up its lawns in the 1980s to create a community garden (“The city came on board when we told them they don’t have to come cut our grass anymore,” Ellis quips), and about five years ago it launched Aquaponics 707, a closed loop system in which plants and fish are grown side by side without the use of soil or pesticides, while monitoring tools alert centre staff to any changes in growing conditions.

Right now, the centre grows a variety of herbs and lettuces (in addition to plants grown as fish food), alongside massive tanks teeming with tilapia. The fish and produce are then sold to community members and local businesses supportive of sustainable farming methods, with the profits from those sales pumped back into the centre’s programs.

But as Ellis notes, the perks of having a working fish farm in the middle of Canada’s largest city go well beyond the financial benefits. “This is a public space, not something that’s housed behind big walls in a warehouse at the edge of the city,” Ellis says, explaining that part of the project’s purpose is to make it a showcase for urban farming that might inspire others to do the same. “Most people who come here [to see it] say they can’t believe it – but it’s there.”

Meanwhile, about 2,700 km to the northwest, another indoor farming project is delivering fresh produce to residents of the Opaskwayak Cree Nation, just across the river from The Pas, Manitoba. Located about a six hours’ drive north of Winnipeg, the community was struggling with the same kinds of food security issues that are common throughout Canada’s northern and Indigenous communities. In 2015, they partnered with Korea Agriculture Systems Technology to create an all-season vertical farm within an existing community hall, with the University of Manitoba on board to conduct research into the project’s impact on community health.

The first seeds were planted in February 2016; since then, OCN Smart Farm has produced more than 70 varieties of plants, with the harvests helping to supplement the diets of residents whose options for fresh produce are limited because of income levels and where they live.

“A lot of the produce we’ve grown just isn’t available on the market up here,” says operations manager Stephanie Cook. “We have different types of fruits and vegetables: radishes, onions, strawberries, leeks – 17 types of lettuce! I’ve been introduced to 30 types of produce I never even knew existed. Now I go to the grocery store and I’m comparing, ‘Okay, if we put that on the market, how much would we sell that for?’”

The “smart” part of the OCN Smart Farm comes from the technology used to grow the plants inside the facility. Red, green and blue LED lights – with options to control UV and infrared light, plus other settings – are used to mimic sunshine. A computer controls temperature and moisture in the room while monitoring carbon dioxide and nutrient levels for each plant species. Very little water is wasted in the soil-free environment, with about 90 per cent recycled through the system.

As one of the people who was involved in the project from the very beginning, Cook is an enthusiastic ambassador for the project, noting the impact it’s already having on health levels in a place where roughly half of residents are diabetic. While university researchers study the role that fresh produce can play in improving community health, Cook and her team are focused on fine-tuning their processes and experimenting with different varieties while they collect data that demonstrates how their set-up can be replicated in other remote communities.

“After all the years of research, we’ve discovered that because we’re so fresh, we can be four to eight times more nutritious than grocery store vegetables,” she said. “There’s enough of a need out there to sell and share this technology with other outlying communities.”

Canada is big on agriculture. The sector contributes about $110 billion annually to the nation’s GDP and employs one in eight Canadians – figures that help make us, despite our relatively small population on a global scale, the fifth-largest agricultural exporter in the world. These numbers are even more impressive when you realize our northern climate and challenging geography means that only about five per cent of the nation’s landmass is cultivated for farming – and even those arable lands are feeling the pressures of climate change and urban encroachment.

Small wonder, then, that Canadians are at the forefront of figuring out new ways to grow more food more efficiently in more places, whether it’s community centres, northern climes… or pretty much anywhere you can set up a building.

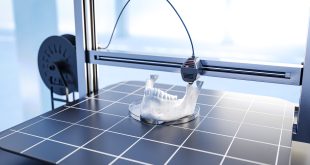

In a business park surrounded by some of Ontario’s richest farmland, one of Guelph’s newest ventures is a fully automated vertical farm, a 45,000-sq.ft. facility that can produce greens like broccoli, pea shoots and arugula from seed to sprout in less than a week.

Founded in 2011, GoodLeaf Farms established its pilot test farm in Truro, Nova Scotia, in 2015. With the help of researchers from Halifax’s Dalhousie University and the University of Guelph, the company used years of data gleaned from developing new varieties and growing techniques to break ground at its Guelph facility in March 2019. GoodLeaf began selling product through Loblaws and Sobeys stores in August and Juanita Moore, its executive director of operations, believes this is only the beginning for vertical farming in Canada given the advantages it provides over more traditional farming methods.

“It’s a very controlled environment,” she says, adding that no human hands touch the product at any point in the process. “It’s pesticide-free, and we have more control from a safety perspective. We’re always testing in-house to make sure the product is safe before it goes to market.”

While vertical farms require more electricity to run than traditional farms, Moore says that impact is offset by the much smaller transportation footprint and total elimination of fertilizers and pesticides from the growing cycle: “I really believe this is the future of farming. There’s only so much land, and it’s important that we find ways to make our land more effective.”

Year-round availability, fresher product, reduced labour costs through automation, and reduced pressure on our land and water resources are additional reasons for incorporating more technology in our food production, says Youbin Zheng, a professor at the University of Guelph’s School of Environmental Sciences; although, he adds, there are some potential challenges for vertical farming as well: “It can be energy-intense – for lighting, etc. – and you need more skilled labour. Plus, we’re not able to grow all foods efficiently [in vertical farms], like grains such as wheat.”

Bringing the benefits of smart farming out into the field (literally) is what institutions like Olds College intend to do. Established in 1913 as an agricultural college about 90 km north of Calgary, the school launched its smart farm on 110 acres in the summer of 2018 to help industry, students and researchers develop “smart connected” technologies for crop farming. (The school added to this acreage earlier this year with a generous donation of almost 320 acres in nearby Carstairs, Alberta – land that the school will use to expand its smart farm research.)

Stationary soil monitors, digital weather stations, wireless grain bin sensors, UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles) and a wireless mesh network providing WiFi to the entire farm are some of the high-tech tools used to help students and researchers gather data and make evidence-based decisions to improve field productivity and sustainability.

While all this technology may seem out of place to folks who aren’t involved in the day-to-day business of growing our food, the truth is that farmers have been on the cutting edge longer than you might think. “Technology and innovation have always been inherent in agriculture,” says James Benkie, dean of agriculture technology at Olds College, pointing out that even the humble tractor was at one point a technological leap forward for the agricultural sector.

But what we’re starting to see more and more in the past decade, Benkie says, is agricultural producers coming on board with the idea of “the internet of things,” the catch-all phrase for systems of interrelated computing devices, mechanical machines and objects or animals that collect and transfer data over networks – data that can be used to help farmers make decisions faster and more efficiently. The same types of wires and circuits that allow, say, a self-monitoring home to become more energy-efficient can be used to collect data on temperature, humidity, wind speed, pest infestation, soil content – any factor that might affect growing conditions for crops or livestock raised either indoors or out in the field.

For Olds, adopting this forward-looking approach to agriculture is attracting attention. The first phase of the project attracted over $1 million in cash contributions from 14 industry partners, with several projects being developed in its first four months. In addition, in August the federal government announced $1.9 million in funding to help Olds College hire more technical specialists and buy agricultural equipment and advanced sensor technologies for the Smart Farm’s Phase 2. About $10,000 of that went to support AgSmart 2019, an event hosted by Olds College this past summer that introduced farmers, students and academics to cattle-ranching drones, robotic farm equipment and other cutting-edge developments in agriculture technology.

If all this innovation seems a bit head-spinning, that’s a normal response to rapid change – but it doesn’t mean things are going to get any less dizzying in the coming years. The United Nations reports that the world will have to increase global food production by 50 percent over the next 30 years to feed the estimated two billion more of us that will be on the planet by 2050; governments, industry and agricultural leaders are going to be very motivated in the coming years to find every advantage they can to keep up with demand.

Because of this, there’s every reason to believe the agricultural sector – despite its idyllic image in most peoples’ minds – is poised to become the section of the economy that will experience the most drastic technological transformation in the coming decades.

“The industrial revolution is now coming to farming and we’re seeing more technology coming to the field,” Moore says. “I’m very excited by what we’ve already been able to do and also by how much more opportunity lies in front of us.”

Cook echoes that excitement, having seen for herself the transformation within her own community after just a few short years of her farm’s operation. And while she has big dreams about seeing remote and Indigenous communities all over the map become more self-sufficient through the power of “smart” agriculture, she’s also happy to focus on the smaller victories along the way.

“Right now, though, one of my biggest tasks is getting children to eat more produce,” she admits. “If I can get my five-year-old to eat his romaine lettuce and carrots, that’s a step in the right direction.”

BioLab Business Magazine Together, we reach farther into the Canadian Science community

BioLab Business Magazine Together, we reach farther into the Canadian Science community