Researchers at the University of Alberta explore the link between diabetes and exercise

By Hermione Wilson

For Steinback, the link to diabetes in his research is heart disease, which is, according to Boulé, the number one killer of people with diabetes.

Walking by the Physical Activity and Diabetes Laboratory (PADL) at the University of Alberta, you might mistake it for a fitness centre. A large part of the lab is exactly that, a private research gym where Dr. Normand Boulé and his colleagues, Drs. Margie Davenport and Craig Steinback, run their training studies.

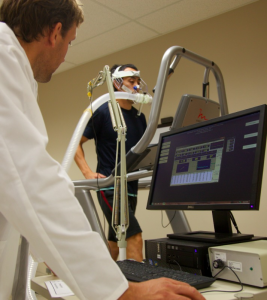

The fitness centre serves as an exercise and physiology lab, and is divided into different subsections. The main section is dedicated to the exercise and fitness testing, while the other sections are for drawing blood, observing exercise capacity and oxygen consumption, and taking other measurements of participants before, during and after physical activity.

Two smaller rooms at the back of the lab are where the more experimental work takes place, where Boulé and his colleagues look at more advanced measures of a participant’s cardiovascular function and how the body responded to different tests.

Since 2010, the PADL has been a part of the University of Alberta’s Alberta Diabetes Institute (ADI) and has made its home on the first floor of the Li Ka Shing Centre for Health Research Innovation. The institute is made up of researchers from different faculties at the university, such as Nutrition (one floor above the PADL), Pharmacology, Public Health, Immunology, and the faculty from which Boulé, Steinback and Davenport hail, Physical Activity and Recreation.

“Our faculty has been part of the [Alberta Diabetes] Institute for a long, long time,” Boulé says. “It’s just more recently that this building became available and we worked hard with the faculty and the Alberta Diabetes Institute, as well as the Alberta Diabetes Foundation, to put this lab together.”

Although Boulé, Davenport and Steinback have physical activity as a common thread in their research work, each of them specializes in three very diverse areas. Boulé looks at how exercise, in conjunction with medication and diet, affects glucose control in people with diabetes. Davenport studies the impact of exercise and sedentary behaviour on maternal and fetal health, while Steinback is mostly concerned with how the brain controls blood pressure and communicates with blood vessels.

The three researchers have their own unique research focuses, but they do find many overlaps in their work where diabetes is concerned. For example, Davenport has in previous studies looked at blood sugar control in women who had gestational diabetes and how exercise could be used as an adjunct therapy in standard prenatal care, along with diet and insulin.

For Steinback, the link to diabetes in his research is heart disease, which is, according to Boulé, the number one killer of people with diabetes.

“Glucose and insulin are not regulated as well [in people with diabetes] and can have a confounding effect on the cardiovascular and autonomic systems,” Boulé says.

Steinback employs a technique called microneurography to study how the body communicates with blood vessels and regulates blood pressure. Using a device called a Nerve Traffic Analyzer, Steinback can record tiny bioelectrical signals that correspond with bursts of activity and elevated levels of stress, and amplifies them.

“We take basically [something] like acupuncture needles and we can place those to record the activity of nerves in the body,” he says. “We can record how the body responds to stress, or your fight or flight response, and that response directly speaks to blood vessels, and that in turn is what controls your blood pressure.”

Using data acquisition software, Steinback and his team can merge these signals with other measurements of blood pressure and blood flow, recorded using ultrasound technology, in order to get a more complete picture of what is going on.

Steinback is also interested in how individuals respond to activities, environments or health conditions that limit their oxygen intake. In the lab he uses gas mixtures to change the composition of the air a participant is breathing through a mouthpiece or face mask in order to simulate breathing at high altitudes. Then he observes how the body responds to the stress.

Steinback is planning a research expedition to the Mount Everest region this fall to study the effects of the low oxygen environment of the mountains on the human body. He plans to study the local population of sherpas and porters and how their bodies have adapted to their unique environment, as well as doing tests on himself and the group of 30 researchers he plans to bring with him. “We’re going to be our own subjects,” Steinback says.

Both Boulé and Davenport have collaborated with Steinback on a number of projects. Davenport uses the same ultrasound and microneurography equipment when she and Steinback are doing work together in the area of cardiovascular regulation.

“We’re looking at how blood pressure is regulated during pregnancy, as well as during complicated pregnancies, so women who have high blood pressure or have diabetes during pregnancy, or are at risk for developing high blood pressure,” Davenport says. “We’re looking at some of the underlying mechanisms that might cause this to happen during pregnancy.”

Steinback and Davenport plan to collaborate in the near future on the impact of sedentary behaviour on blood glucose control and overall health.

“When they both arrived, I could see links more directly with [Davenport] and her gestational diabetes,” Boulé says. “The word diabetes is something I understand a little bit more than some of the stuff [Steinback] does, but I think from a mechanistic perspective, some of the collaborations between [Steinback] and I weren’t expected but have developed as well.”

In the course of their research and the studies that they have conducted both together and separately, Boulé, Davenport and Steinback have uncovered some interesting things about the effects of exercise on human physiology. They have learned, after several studies looking into health outcomes for combining the drug Metformin and exercise, that the two don’t necessarily augment the effect of the other. Metformin is one of the most commonly prescribed medications for diabetes.

“The combination of the two was no better than exercise alone or Metformin alone,” Boulé says. “We don’t have a good happy ending story yet where we can say, ‘This is how you should best try to combine them to have better outcomes,’ but we’re working on that as well right now, how to better combine exercise with these other mainstream interventions.”

They are also learning interesting things about resistance training and whether higher intensity exercises are beneficial not just for athletes and young healthy people, but people with diabetes as well.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, Davenport and Steinback have discovered, during the course of their research into sedentary behaviour, that low energy activities that involve sitting or reclining are independent predictors of long-term cardiovascular or metabolic diseases.

“The idea of not exercising enough or exercising too little is completely separate from sitting too much. They’re very distinct ideas, so we’re looking at both of them,” Davenport says. She is particularly interested in the effects of sitting too much on cardiovascular and metabolic function during pregnancy, about which little is known.

The three researchers of PADL have helped shape the changing protocols for diabetes and pregnancy exercise guidelines. Davenport is currently working on a set of pregnancy and exercise guidelines, and Boulé was recently brought on to work on the physical activity section of a new edition of the Canadian Diabetes Association guidelines.

“Some of our initial successes had a lot to do with really improving the standards of the evidence behind exercise in Type 2 diabetes,” Boulé says. “At the time, a lot of the initial studies were kind of small, underpowered, and a bit varying results, so we did a lot to synthesize the evidence and come out with some really good quality evidence behind the role of exercise.”

Ultimately the work Boulé and his colleagues are doing at PADL will have a lasting impact not only on those struggling with diabetes, but also for anyone – young, old, relatively healthy or living with illness – who wants to live a better, healthier life.

Top: A fitness centre serves as an exercise and physiology lab at the Physical Activity and Diabetes Laboratory. Photo Credit: Craig Steinback

Above: Normand Boulé analyzes a study participant’s oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production during an exercise test.

Photo Credit: Alberta Diabetes Institute

BioLab Business Magazine Together, we reach farther into the Canadian Science community

BioLab Business Magazine Together, we reach farther into the Canadian Science community