University of Saskatchewan Insect Research Facility promises new research into agricultural threats

By Robert Price

Sean Prager has been in love with bugs for a long time.

He began researching bugs during his undergraduate years at Clark University in Massachusetts in the early 2000s. Given a choice between studying fish and mosquitos, he chose mosquitos.

Today, Prager is an associate professor in the College of Agriculture and Bioresources at the University of Saskatchewan. He’s the lead researcher at University of Saskatchewan Insect Research Facility (USIRF), a newly constructed laboratory dedicated to the study of insects and plant pathogens. USIRF isn’t the first of its kind in Canada, but the impressive facility promises to advance research into the bugs that can hurt Canada’s food supply.

Inside the Box

Prager describes the USIRF as “a really big box” with other boxes inside it. Inside those boxes are bugs.

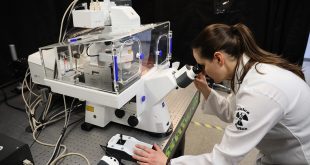

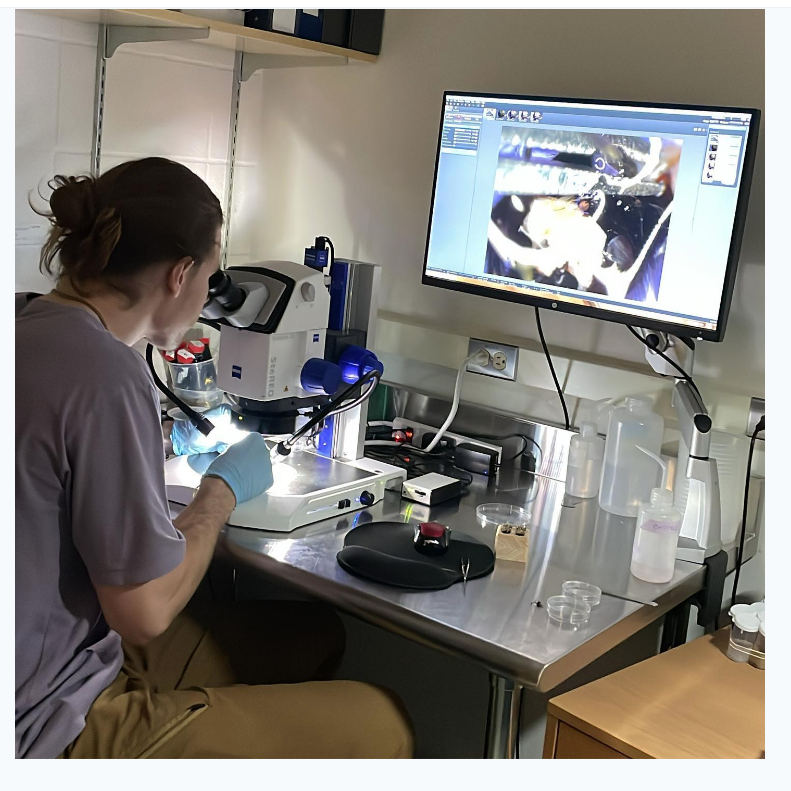

Prager’s explanation of what the 500-sq.-ft. USIRF looks like sounds simple. In reality, the Level 2A containment facility is a startlingly complex ecosystem of pathogen habitats, quarantines, and security measures.

The facility contains rearing chambers for plants and insects. It has freezers, temperature controls and humidity controls, screens and HEPA filters, and workspaces. Traps attract insects and keep them from escaping. Near the doors, negative airflows suck air back into the boxes. Special materials—materials that can be bleached and that are for the most part inorganic—ensure that hungry insects and fungal pathogens cannot eat their way out of the box. The lighting also controls the bugs. Standing inside the facility is like standing inside a dark room: all the lights are red. Insects cannot see the colour red, and so the insects think they’re living through an eternal night.

“Everything inside there is built to prevent things from escaping,” says Prager. “It’s very secure. It’s bio-secure.”

The USIRF serves many purposes. The value of the facility is in, Prager says, “the kinds of research it allows us to do.” A chief concern for researchers is how well invasive species can adapt to Canadian environments. Could a beetle that currently breeds in Australia survive in Canada if it somehow found its way to our shores? Could a plant pathogen survive Saskatoon’s -40C winters?

Without the facilities like USIRF, researchers can only guess what might happen. The quarantined space made possible by the “boxes” that comprise USIRF allow researchers to grow plants, infest them with various strains of pathogens and serve them to exotic insects, and freeze them to see if they can survive a Canadian winter. They can assault the invasive species with pesticides and identify the natural enemies of these invasive species—the predators that will eat those pests. The biological controls inside the facilities allow researchers to play out these insect war games to determine what bug will dominate, and which might dominate us.

“We can bring [novel pests into Canada] and we can kind of expose them, and we can see what we should expect,” says Prager.

The facility uses rearing chambers custom-manufactured by Conviron, a Canadian company. What’s unique about this facility is that the control systems and the insides of the freezers and computer components are all on the outside of each box. This design allows easy access for repair people who could never break the quarantine to enter the chambers.

All the chambers are wired together to what Prager calls a “central brain”—a central management system that’s run by full-time staff. The central management system controls the temperature, lighting, humidity, and other elements of each chamber. If something goes wrong—if quarantine is broken, if there’s a power outage, if a temperature rises above tolerance levels—the alert system texts a person monitoring the research to let them know that something has gone wrong.

“That practice is important in general, but it’s also important for something like this because it’s a quarantine,” Prager says. “You don’t always have people do it all right. So just like a lot of things, there are mechanical safeguards—the last line of defense beyond good practice.”

Getting ahead of the bug

This research has long-term implications. Researchers determine what strains of cultivars prove resistant to particular pathogens and insects. A breeding program gives researchers the time to cultivate new strains of seeds and grains to get ahead of invasive species. This work is important because, as things currently exist, the response to insects and invasive species can be long and frustrating.

As it is now, if a bug were to show up somewhere in Saskatchewan—let’s say it traveled by truck from a potato farm in Idaho and set up its colony in a field 150 km outside Saskatoon—farmers would first have to find that bug, and they might only discover the bug when they see their crops are under attack. An investigation would begin. Researchers would have to determine what type of bugs they were dealing with, map the pest’s locations, and then determine what kind of insecticide is best able to kill the bug without harming plants or killing beneficial insects. If you don’t have a registered insecticide that can kill those bugs, then the agricultural industry will have to go through a long process of obtaining a legally controlled insecticide. Farmers might have to register for an emergency exemption. They might be denied. The entire process could take four to six years before farmers can mount an aggressive attack on the pest, and those years could devastate entire farming communities.

With the research being done at USIRF, researchers can identify possibilities that could confront farmers and help develop plans to counter them. Plant breeding takes decades, but if researchers know that such a bug might appear one day, whether by accident, by circumstance, or through the machinations of climate change, they can breed robust cultivars, formulate and gain approval for new insecticides, and plan for what to do in an emergency.

“You need to be way ahead of them,” he says. It is work that can take decades, as Prager knows well. “I’ll be like, you know, at the back end of my career before anything is released that anyone actually uses,” he says.

Building the Dark

The construction of the facility took almost six years to complete. When Prager arrived at Saskatchewan in 2017, he was shown where his lab could be. The space had been carved out originally for a facility like the one they’ve built, but at the time the space was used for storage.

Prager had a blank slate and set about building what became the USIRF. The first step in building the facility was gathering the funds. They obtained funding through the Western Grains Research Foundation, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Saskatchewan Canola Development Commission, the Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, the Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission, and the University of Saskatchewan. Delays during the COVID pandemic led to an increase in costs and Prager had to go searching for more money. He found it.

Now, after six long years, they have the facility ready to go. After a few more checks and approvals still to come, and once all the journalists have finished taking their pictures, Prager will establish quarantine and the bugs will be locked in a dark box.

BioLab Business Magazine Together, we reach farther into the Canadian Science community

BioLab Business Magazine Together, we reach farther into the Canadian Science community